Our trip up the west coast was an exercise in patience. It was a series of one- or two-day hops from one harbour to the next, followed by five or so days of waiting for favourable weather conditions before we could make the next hop. Our hops usually meant motoring into as little wind and waves as possible while watching carefully for crab traps. Crab traps being the main hazard on this trip.

Crab traps consist of the trap, which sits on the ocean floor, attached to a long rope which is attached to a buoy which floats on the surface. From that buoy is another rope. It floats on the surface and has a buoy attached to its free end. Sometimes there is even an additional floating rope and buoy. The floating line makes it easier for the fishermen to snag the rope and pull up the trap. Unfortunately, the floating rope is also easily snagged by unsuspecting sailors.

To add to the challenge of avoiding traps, the buoys are not all the same. Some are neon orange or bright green, but many others are white or even black. The white buoys turn brown with dirt as they age. Additionally, the buoys are usually covered in green growth. The longer they have been in the water, the more growth they accumulate and the harder they are to see.

The traps are usually spaced out in long rows—sometimes with as many as 20 traps in the row. These rows make them fairly easy to avoid. Once one spots the first trap in a row, one can parallel the line or, if necessary, carefully choose a spot to cross the line between the traps. As I said, the traps are usually placed in rows, but not always. Often there are rogue traps that are all by themselves. Also, the traps can be laid out in such a way that they have no perceivable order to their placement. Finally, the traps are most predominant within 10 to 20 miles of a harbour and in shallower water.

We have done the trip along this coast twice now–once going south and once heading north. We used different strategies to avoid the traps on each trip. Our strategies worked well, until they didn’t.

On our way north a few weeks ago, we left Crescent City, California, bound for Newport, Oregon, on a beautiful, sunny afternoon. Strong southerly winds were forecast for the next afternoon, but we hoped to arrive in Newport before they built too much. In fact, we hoped to use the southerly winds to sail for some of the trip—something we had not been able to do much on our trip north. While we still had daylight, we worked our way north and several miles offshore, hoping that distance from shore and deeper water would lessen our risk of snagging a crab trap once darkness fell. Our plan worked for us, but during the night, our friends on Unbelievable hit a trap. Fortunately, by quickly putting their engine in neutral, their boat slowed enough that the trap dropped free, and they were able to resume their way north.

At sunrise on the second day the winds filled in from the south as forecast. We rolled out the jib and were able to sail. It was a pleasant relief to switch off the engine and enjoy making our way north without the hum of the motor.

Unfortunately, our weather window was closing sooner than we had expected. Gusts of 40 kts were now forecast for that afternoon. Fortunately, we were just a few miles from Coos Bay, Oregon. If we changed course, we could be there in time for breakfast! We decided to head there. We were disappointed that we would not be 60 nautical miles closer to home by the end of the day, but it was the prudent thing to do. Besides, we were having a very pleasant sail, and at our current speed, we would arrive at the Coos Bay bar at slack tide–perfect timing. We turned our bow towards Coos Bay.

The wind and waves continued to build as we made our way to the harbour entrance, but they were from behind us, so we were comfortable. Cambria handled them easily. The seas were choppy with many white horses making it difficult to see the crab traps. As we neared Coos Bay, the traps became more numerous. It became difficult to discern a pattern in how they were laid out. I stood in the cockpit, watching forward, scanning for traps. We were about a mile from the Coos Bay bar when I spotted a trap dead ahead of us. I turned to avoid it. Perhaps I zigged when I should have zagged, but I snagged it. I could see the floating line and buoy streaming out from under our stern. I tried to turn back the way I had come. I thought that by reversing my course, the line would float free, but it didn’t. After a few attempts to sail away from the buoy, we furled the jib, hoping that the trap would float free as we drifted. It did not.

Next, we used our boat hook to grab the floating line and pull, hoping to free it from whatever held it. We were not successful.

Finally, Sharlene dug out my mask, snorkel, and fins while I pulled on my 3mm wetsuit. Unsurprisingly, the wetsuit that kept me a bit too warm in Fiji was useless in the waters of Northern California. I knew this would be the case, but thought it was better than nothing. I jumped into the water but couldn’t see what was keeping the rope under our boat. The visibility was poor. I could see the rope was not caught on our prop or prop shaft, but it disappeared from sight before I could see what held it. In addition to the poor visibility, the seas and wind had been building, so Cambria was heaving up and down as I swam under her and peered into the murk. Soon, the cold was getting to me, so I clambered back aboard.

As I dried off and tried to warm up, we discussed our options. The weather wasn’t going to get any better. Slack tide for crossing the Coos Bay bar had passed by now. The more time that went by meant the bar would get increasingly difficult to cross.

Thankfully, there is a U.S. Coast Guard station at Coos Bay. I called them on the radio. After explaining our situation, they dispatched a vessel and crew to come and give us a hand.

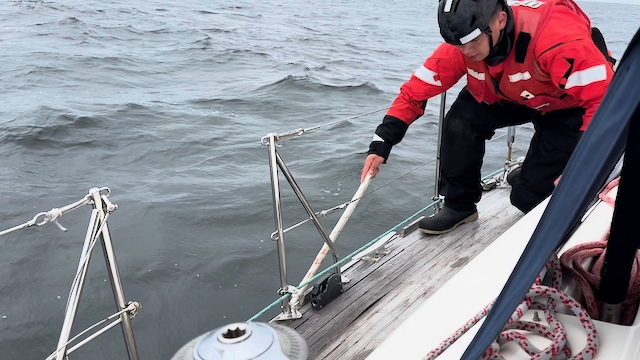

The initial plan was to tow us into Coos Bay, but once they arrived and assessed the situation, they decided to put a Coast Guard member aboard Cambria to try and free us from the crab trap. They carefully manoeuvred their vessel alongside Cambria—close enough for the sailor to step aboard. He brought with him a long rope with a heavy shackle tied to its centre.

The young man and I positioned ourselves at the stern of our boat, he on one side and I on the other. We each took hold of the rope, near the middle and on either side of the heavy shackle. Slowly, we lowered the rope into the water in such a way that it caught the crab trap line that streamed out from Cambria’s stern. The heavy shackle made the line sink below our rudder and other parts of Cambria’s underbody. Slowly we walked up each side of Cambria, he on one side and I on the other, while pulling the heavy rope. This caused the crab trap line to sink further down. Soon, Sharlene spotted the trap line and its floats beside our boat. We were free! A few shakes of the rope we held, and it freed itself from the crab trap rope. We drifted to windward, leaving the crab trap behind.

Because we were sailing when we caught the crab trap, the engine wasn’t running; therefore, there was no damage to our prop or prop shaft. We fired up the engine, and all was well.

The Coast Guard cutter drew in close to Cambria, ready to pick up its crew member. Unfortunately, the waves had continued to build while we were working to free ourselves. I did my best to keep Cambria pointed into the waves as the Coast Guard cutter drew alongside. I was told to put our engine in neutral as they got close, so I soon lost steerage and Cambria turned broadside to the waves. The cutter hit us quite hard as their member stepped back on board. Fortunately, the damage was minor, and we were happy to be free from the crab trap.

We pointed our bow towards Coos Bay. By this time, we had drifted several miles past the bar entrance, which meant motoring against the wind and waves. We were barely able to make four knots. We were slow but fine. We would be able to make it into Coos Bay without help; still, the captain of the Coast Guard vessel insisted on staying with us until we were safely across the bar and into the Coos Bay harbour. We felt like royalty as we crossed the bar and approached the marina with our Coast Guard escort. As we approached our slip there were two Coast Guard members waiting for us at the dock, clipboards in hand, ready to complete a report.

In the end, we were quite lucky. There was no major damage, just a couple of bent stanchions and my bruised ego. On this trip, we have sailed a little over 15,000 nautical miles, and we almost made it home without a major incident. Ah well, better luck next time.

Well that is a fun adventure! Man – I bet that water was COLD. Thanks for sharing this story. Well written!

LikeLike

Thanks and yes the water was cold. It took me the rest of the day to warm up 😃

LikeLike

So glad the coast guard was able to help you out! Glad you and Cambria are all ok!

LikeLike

Thanks! It was a little stressful but turned out okay.

LikeLike

Hi guys,

Hello from Nova Scotia.

We hope you are doing well.

Would anything heavy work to get the line loose or did the shackle do something specific?

Did you find a marina for Cambria?

Cheers,

Mike & Shirley

LikeLike

Hi Mike! Anything heavy would work. It wouldn’t have to be a shackle.

We got a slip in Maple Bay! It’s actually closer to home than when we were moored in Brentwood.

LikeLike